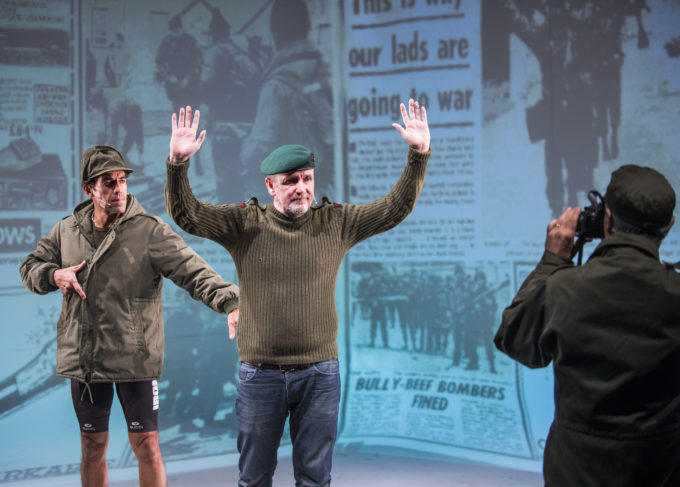

Arts and culture publication Corrugated Wave caught up with University of Sussex’s Professor Lucy Robinson to discuss Lola Aria’s MINEFIELD, which opens at Attenborough Centre for the Creative Arts this week, running from 15-17 November. Lucy is a Professor of Collaborative History and has written extensively on the Falklands. For Corrugated Wave’s full feature on MINEFIELD and much more keep an eye on their website.

How did you become involved in Lola Arias’ work? Have you been brought in to give this talk because of your expertise on the Falklands war’s trauma or were you involved earlier in the project?

I hadn’t been involved in the project earlier, but I had seen the piece previously and had absolutely loved it. I had been deeply moved by it, and it had stayed with me. It really resonated with the work that I had done on what happens to soldiers who tell their stories about the Falklands war. I could see the echoes of the stories that the veterans had told me, but even more impressively, Arias had truly given the veterans their own voice. It’s such a difficult thing to do ‘to give someone a voice’, and I think it’s something that a lot of us aspire to as historians but this piece actually does it, and more than that, it lets those actor participants analyse the piece for themselves.

What we would really like is to situate Lola Aria’s MINEFIELD historically through your research…

You say in a note in “Explanations of post-traumatic stress disorder in Falklands memoirs: the fragmented self and the collective body” that “the field of Falklands memoirs has been increasingly dominated by non-officers and by two groups; the Paras and the SAS.” Could you give us a brief overview of the academic work around Falklands memoirs and what you have written about yourself?

The Falklands War sits at an important place for historians. It coincided with a new understanding of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, new media technologies (like the Walkman) and the rise of new work by historians on war and the nation (people like Lucy Noakes, who was at Sussex, for example). It also changed the way that people market their stories about war. The military memoir market is a big one, but they are usually initially dominated by officers at the top and then the stories from the ranks emerge much later. The first Falklands memoirs were by journalists, and then by officers involved: Julian Thompson No Picnic or Nick Vaux’s March to the South Atlantic in 1985 and 1986. Since then there has been an increase in the proportion of accounts written by ‘ordinary soldiers’. In 1997 about two thirds of the accounts available were written by officers, since 1997 about two thirds were written by ‘ordinary soldiers’.

I studied 47 written by military personnel and published in text form as well as edited life history collections , the two published islanders accounts, those by war correspondents and artists, and reworked diaries , collections of letters , poetry, paintings, cartoons, etc. There are lots of different ways to tell a soldier’s story.

Could you tell us a little bit about the collective military body you discuss - the rituals, the totems, the belonging - and discuss any connections you feel this might have with the work by Lola Arias (if you do feel this)? The way you talk about the “imagined collective body” and the link between their return and PTSD’s onset are also fascinating.

The military has to train you to put the collective before yourself. Military training breaks down the individual and instead builds a collective military body that will work together, without even questioning it. The smallest rituals, a tea break, a shared cigarette, the stories that they tell each other, the darkest jokes that they make are all ways of building a collective resilient body of men. It is often when the individual loses that collective body that they can break down, sometimes returning from war is incredibly difficult, and evidence suggests that it is when individuals leave the military all together that they are even more vulnerable to PTSD.

Tickets for MINEFIELD can be bought here.