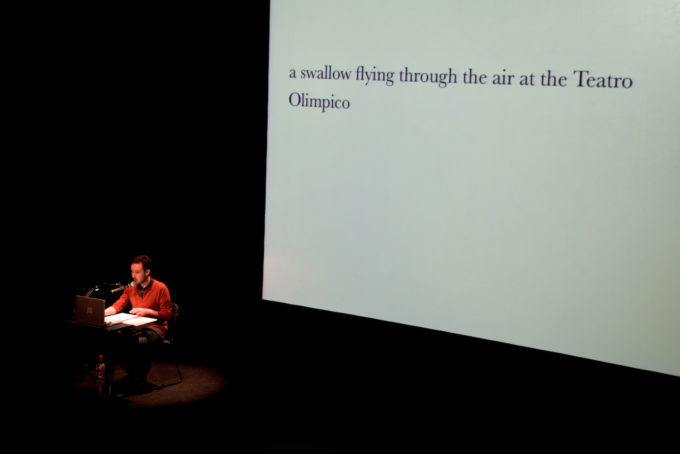

In Place of a Show is a performative lecture given by Augusto Corrieri, artist, performer and University of Sussex academic, focusing on what happens inside theatres when nothing is happening. Ahead of its appearance at the Attenborough Centre for the Creative Arts on 27 September, we caught up with Augusto to learn more.

You talk about non-human entities inside the theatre, what do you think about the physical position of spectators inside a theatre which has differed through history?

Whatever the positioning of audiences - close to or far from the stage, ‘involved’ or ‘detached’ - spectators occupy a central place: without a spectator, the show can’t go on. So the presence of spectators is what makes theatre, it is what inaugurates the situation of theatre: on one side someone does something, on the other side someone observes. This co-presence, historically, is what I would call the situation of theatre.

What made you focus your work on the non-human elements that characterise the theatre? Do these historical features of the four theatres you discuss on your lectures have something to say about today’s theatre?

I firstly got interested in theatre buildings, particularly what we might call ‘traditional theatres’ (with a raised stage, curtains, balconies, etc) because of the strange absence they seem to produce. Stand inside an ‘empty’ theatre, and it is striking just how much the human element is in fact really present. It is like laying out a set of clothes (a shirt, trousers, shoes, etc), with no body wearing them: the human is in fact very present, through its absence. So then I started to think: hold on, but what about the actual space itself? Surely the theatre’s material components are more than just cyphers of something that is missing? What are the buildings up to, what are they doing? In a sense the background became the foreground, and the human element lost some of its centrality. There is this shift, if you will, from an anthropocentric perspective, to an ecocentric one.

You primarily focus on the visual non-human elements that make up the theatre such as the curtains, seats, walls, doors… Do you think non-visual elements, like sound, can also have an impact when examining what happens inside theatres when nothing is happening?

This is very interesting to me, and I haven’t focused so much on this aspect. I have wondered about ghosts a lot though, since whenever I tell someone about my research into empty theatres, inevitably the subject of ghosts comes up. It strikes me as deeply problematic that a sound in an empty theatre should be attributed to, shall we say, ‘human ghosts’. It shows just how much we’d rather attribute agency to humans (present or absent), than to the possibility of other forms of life or matter inhabiting this space. What is mysterious to me isn’t the ghost or the supernatural: it is that you might have forms of plant life living in the theatre; or that you might have a termite colony (this happened in the theatre I visited in the Amazon, the Teatro Amazonas, which at one point almost got eaten up by termites). There is an ecology of non-human sounds here, but when faced with any acoustic evidence - a thud, a scraping, an unexplained high pitch sound - our brains seem to go to the supernatural for an explanation. Amazing, really.

What made you pick these four theatre buildings to discuss in your lectures? (Vicenza Teatro Olimpico, Munich’s Baroque Opera House, London Dalston Theatre, Teatro Amazonas)

They all are representative of what has been called the Italian theatre model, or the proscenium arch theatre. All bar one (Dalston), they are presently standing, though they function a bit like museums: people largely go to visit these theatres, as theatres, not as places used for shows. And this project looks at what else theatres are for, what else they might accommodate, or ‘do’, other than putting on a show. The four theatres also seemed to volunteer themselves, or if you like impose themselves, as I was researching the topic, partly out of accident: Dalston Theatre, now demolished, was literally where I was living when I started the project. Amazonas was a bit of a dream project, after seeing Herzog’s film Fitzcarraldo years ago.

Do you think it is important to deliver In Place of a Show in both academic and non-academic scenarios?

I don’t know that it’s important to do so, but it certainly has been interesting to cross these worlds a bit, showing the lecture one week at Sadler’s Wells, and the next at an academic conference, without changing the language or the address etc. I’m a big fan of essayists who seem able to collapse the academic and non-academic register (think Susan Sontag, John Berger, Maggie Nelson), bringing philosophy into conversation with quite accessible literature and ideas. I’m not saying I’m doing that, that would be a bold claim, merely that I’m a fan of those who do. It is a strange or hybrid art form to me: even just showing a photograph, quite alone, can ‘do philosophy’, but it sort of needs the right framing, or the right silence, or playfulness, in order for it to come alive in a certain way… I’ll tell you more once I figure it out!